Essays

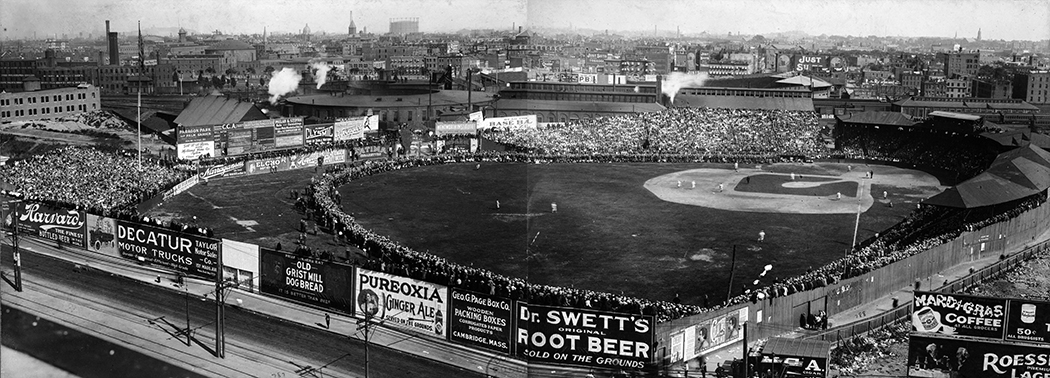

Between 1860 and 1920, Americans grappled with the demographic and political changes of modernization. American baseball team owners used furniture selection and arrangement to invite upper- and middle-class, native-born white men and women to the center of spectatorship and to marginalize non-white, immigrant, and working-class fans. Owners installed a new type of seating, the opera chair, to tame rowdy male audiences and protect the bodies of white women who attended frequent ladies’ days. In newspapers, owners and sportswriters stereotyped spectators by seating section. Fans embraced, and at times resisted, the status imposed upon them through stadium design. A close reading of the interior landscape recorded in newspaper descriptions and photographs reveals spaces divided into hierarchical groups designed to assuage the anxieties of bourgeois white audiences. Professional baseball teams invited all into communal spectatorship to watch the national game but segregated fans in pursuit of profit.

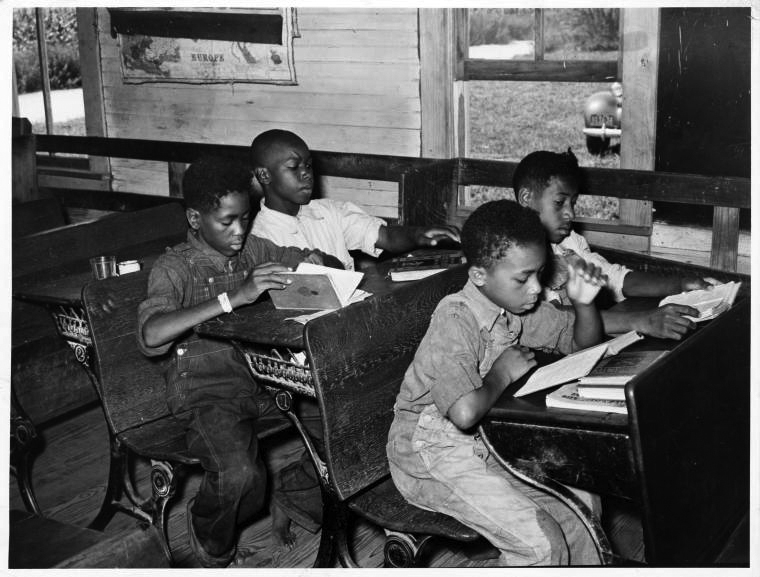

Between 1870 and 1920, American manufacturers designed furniture that re‐shaped the sensorial experience of office work. To help businesses inculcate efficient practice, furniture re‐shaped the posture of employees, programmed their actions, and determined sight lines, soundscapes, and circulation patterns. In the catalogs, textbooks, and trade journals they published, manufacturers gendered and racialized furniture and occupations. By 1920, White‐owned businesses adopted methods built upon standard mass‐produced furniture that affixed White male clerks to their desks and transferred the responsibility for moving information through the office to middle‐class White women. Understanding the historical use of furniture to shape demographics in the twentieth century office opens possibilities and opportunities for new paradigms in workspaces.

Whether we inhabit a desk in a classroom or office or occupy a seat on a train or in a theater our bodies are enveloped, supported, manipulated, and controlled through the form and operation of furniture that is seldom noticed. Ubiquitous, intimate, and often compulsory, commercial furniture (institutional furniture used outside the home) is a powerful resource for elucidating politics in the public sphere. This dissertation demonstrates that between 1840 and 1920 manufacturers produced commercial furniture intended to teach postures, behaviors, and interactions suited to competencies expected of occupants as compliant citizens and industrious workers.

Late nineteenth-century examination furniture disguised clinical characteristics within a skin of domesticity to help physicians shift their services from homes to professional offices and thereby establish cultural authority. Furniture manufacturers carefully considered the visual acuity of middle-class women as decision makers trained by advice literature to

expect specific types of objects within a moral middle-class home.

expect specific types of objects within a moral middle-class home.

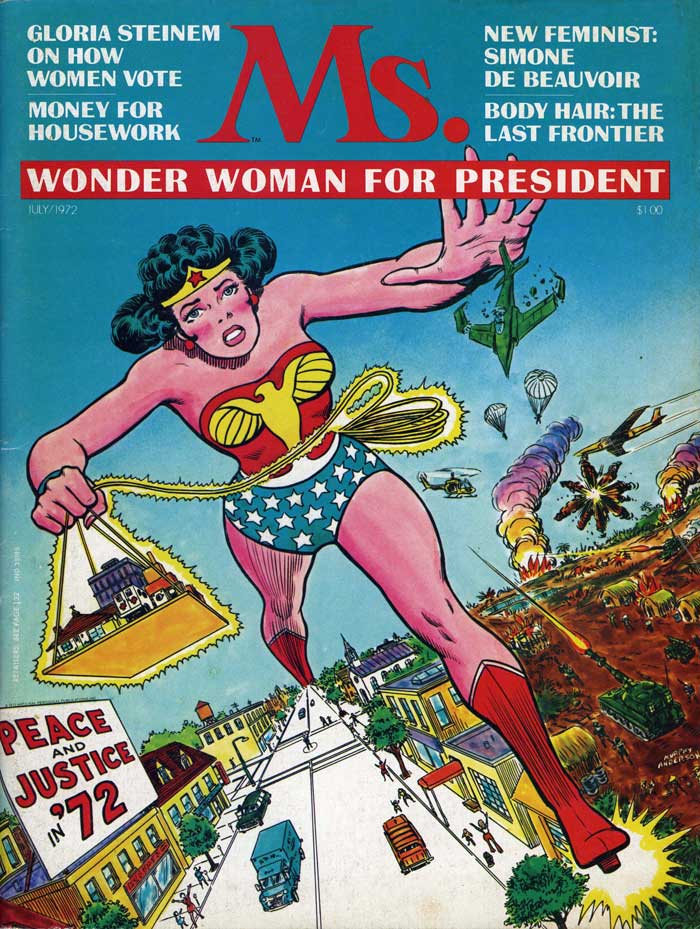

Women designers faced considerable tensions between family and career in the mid-twentieth century (and continue to face today). Some opted for professions in place of family, others abandoned thriving businesses to raise children, returning years later to pick up where they left off, or to take off in completely new directions. Still others found innovative solutions to balance their lives as professionals, wives, and mothers.

Through commerical leisure, American women leveraged a newfound purchaing power to relax conservative norms of courtship.

Tied to the Desk: The Somatic Experience of Office Work, 1870–1920.

Tied to the Desk: The Somatic Experience of Office Work, 1870–1920. PhD Dissertation: Docile by Design: Commercial Furniture and the Education of American Bodies.

PhD Dissertation: Docile by Design: Commercial Furniture and the Education of American Bodies. Art & Science of Examination Furniture

Art & Science of Examination Furniture Parsons Women: Designing a Career.

Parsons Women: Designing a Career. Buying Time: Canoeing and the Commercialization of Leisure in New England, 1890-1920

Buying Time: Canoeing and the Commercialization of Leisure in New England, 1890-1920