Modern American History, July 2019

Figure 1. Frontispiece for The Family Doctor; or, Mrs. Barry and Her Bourbon, Boston, 1868. Sinclair Hamilton Collection of American Illustrated Books; Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

I

n 1868, Mary Spring Walker illustrated the frontispiece of her temperance novel The Family Doctor with an image of a middle-class woman ensconced in her parlor under the intense gaze of a bespectacled doctor (Figure 1). The matron of the house sits at ease in her upholstered armchair in front of a fireplace, her feet resting upon a hassock surrounded by concerned family members who witness the doctor’s inspection. Two small medicine bottles—the only scientific equipment visible—barely intrude on the scene. Middle-class American readers of The Family Doctor would have been discomfited if this scene had been depicted in a hospital instead; Walker understandably set the tableaux in the parlor of a private home where a family doctor was expected to wait upon his patients.

Figure 1. Frontispiece for The Family Doctor; or, Mrs. Barry and Her Bourbon, Boston, 1868. Sinclair Hamilton Collection of American Illustrated Books; Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

I

n 1868, Mary Spring Walker illustrated the frontispiece of her temperance novel The Family Doctor with an image of a middle-class woman ensconced in her parlor under the intense gaze of a bespectacled doctor (Figure 1). The matron of the house sits at ease in her upholstered armchair in front of a fireplace, her feet resting upon a hassock surrounded by concerned family members who witness the doctor’s inspection. Two small medicine bottles—the only scientific equipment visible—barely intrude on the scene. Middle-class American readers of The Family Doctor would have been discomfited if this scene had been depicted in a hospital instead; Walker understandably set the tableaux in the parlor of a private home where a family doctor was expected to wait upon his patients.

Between 1890 and 1930, physicians in the United States shifted the primary location of medical service for middle-class consumers from patients’ homes to practitioners’ offices. Guided by medical advice books and trade literature, doctors outfitted their offices with objects designed to signal legitimacy through visual cues.[1] To ease the transition from private home to professional office, manufacturers produced exam furniture that coordinated with middle-class parlor aesthetics, blurring the line between public and private, occupational and familial, masculine and feminine.[2] In 1873, surgeon J. Marion Sims described the widespread use of examination chairs primarily for their psychological function: “For all practical purposes it is really no better than a common table; but any patient would sit in the chair without nervous agitation. The patient once seated, is told that the chair is only a couch, and she is requested to lean back and extend it horizontally by her own weight.”[3] The comfort of women proved a particular concern because they were perceived as the gateway to family patronage, but also because of the need to preserve, as one pioneering gynecologist put it, “the sanctity of the female modesty and chastity” during examinations.[4]

Before the advent of modern medical practice, physicians in the United States struggled to support themselves and their families. Until 1870, most spent hours traveling back and forth over the rutted roads of rural communities to answer calls for treatment. Income was limited by the small number of patients a doctor could possibly service in such geographically dispersed locations. Homeopaths, midwives, eclectics, purveyors of patent medicines, faith healers, and electricians siphoned off many customers. Authority was difficult to establish while the barrier to medical practice was so low: as late as 1894, the Oklahoma Territorial Board of Health registered anyone with a diploma from a medical school or a sworn affidavit that they had lost their diploma, and eleven states still had no requirements for licensing in 1895. Sensational newspaper reports—such as one 1885 article describing a traveling doctor who had caused the eyes, ears, and nose of a patient seeking cancer treatment to slough off her face—described the horrendous doings of quacks.[5] This distrust of doctors, even of medical school graduates, was memorably fictionalized by Henry James in The Bostonians; the character Doctor Selah Tarrant seemed to the young maiden Olive Chancellor “a charlatan of the poor, lean, shabby sort,” not least because his “temporary lair” was an untidy wooden cottage facing an unpaved road.[6]

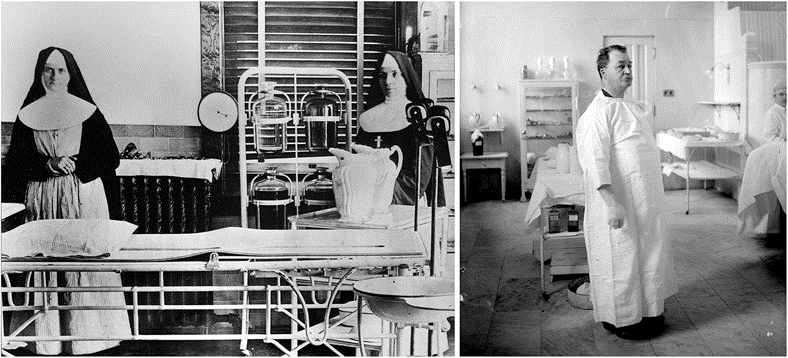

Figure 2. Operating room, St. Mary’s Hospital, Rochester, Minnesota, 1893 and Dr. Nicholas Senn of Chicago in his operating chamber, 1907. Minnesota Historical Society, Chicago History Museum.

Figure 2. Operating room, St. Mary’s Hospital, Rochester, Minnesota, 1893 and Dr. Nicholas Senn of Chicago in his operating chamber, 1907. Minnesota Historical Society, Chicago History Museum.

Steeped in an ethos of self-reliance, middle-class Americans believed that common sense presented the best approach to health care, and that their home was the logical place to treat illness. Before the twentieth century, medical treatment was rarely more successful in institutions than in the home, and usually associated with infection and death. Home remedies, administered mostly by women, were the primary treatment. Usually a physician was only called after a home cure failed. Only the destitute and those with no family went to dispensaries and hospitals, where they suffered in discomfort and fear upon metal chairs, metal tables, and metal beds within stark-white, tile-covered rooms lit with glaring light from naked windows (Figure 2).[7]

But by the 1890s, the widespread use of antiseptic practices, along with other technological developments and rapid urbanization, began to improve the outcomes, efficiency, and profitability of general practice. Administration of anesthesia was a skill that gave medical school graduates an edge over other healers. In growing cities, paved roads, streetcars, and subways decreased travel time and cost for patients to visit a nearby professional office. Rather than being randomly summoned to house calls by messengers sent from patients’ homes, physicians conveniently scheduled appointments during regular business hours with the newly invented telephone. A more efficient practice kept overhead costs low and fees within the financial reach of middle-class consumers.[8]

Technological conveniences, however, also fostered competition. American women proved savvy shoppers for medical goods and services.[9] As the primary overseers of a family’s health in the home, women were logical decision makers for care in the office. Female patients comparison shopped for the lowest cost among licensed, unlicensed, and alternative practitioners. Competition was compounded by a growth in licensed physicians, as the number of medical schools increased from 52 in 1850 to 160 in 1900, and annual graduates, from 3,241 in 1880 to 5,747 in 1904.[10]

Physicians who reassured middle-class women through a carefully designed interior stood out in a chaotic market. In 1871, Harper’s Weekly lauded one Detroit Medical College professor for telling graduates to banish from their work spaces all skulls, anatomical illustrations, and splints, as well as every other “sign of your professional occupation,” in order to put sick women at ease.[11] In a widely read handbook, The Physician Himself, first published in 1882, the author and physician Daniel W. Cathell advised new doctors that women “have more sickness than males, and the females of every family have a potent voice in selecting the family physician.” Cathell warned that “the public, and especially the female portion of it, with eyes as of a microscope, takes cognizance of the associations and of a thousand other little things regarding medical men … every circumstance in your appearance, manners, walk, conversations, habits etc., will be closely observed and criticized in order to arrive at a true verdict.”.[12]

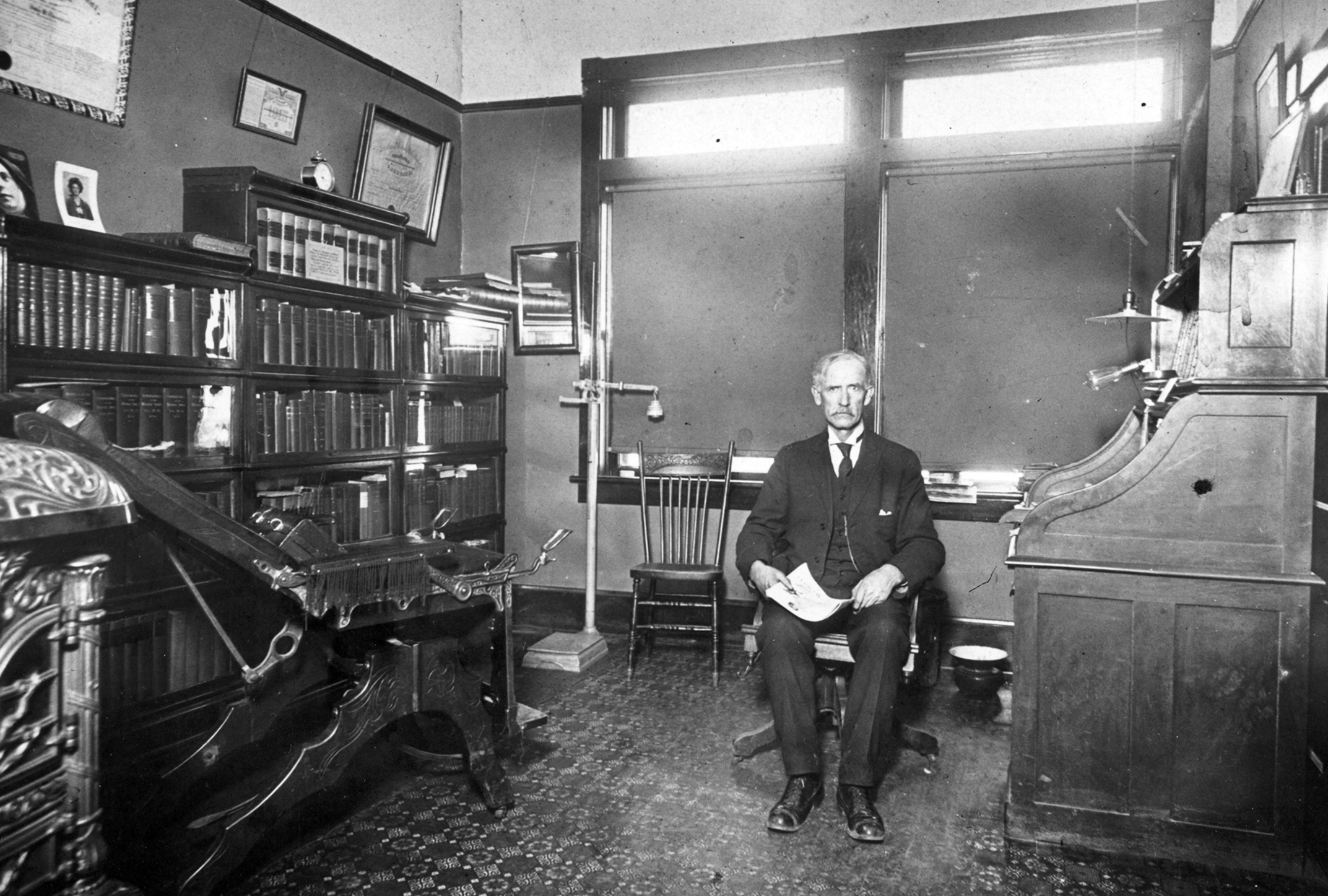

Figure 3. Doctor R.E. Gray’s office in Garden City, Kansas in 1901. The Kansas State Historical Society.

Figure 3. Doctor R.E. Gray’s office in Garden City, Kansas in 1901. The Kansas State Historical Society.

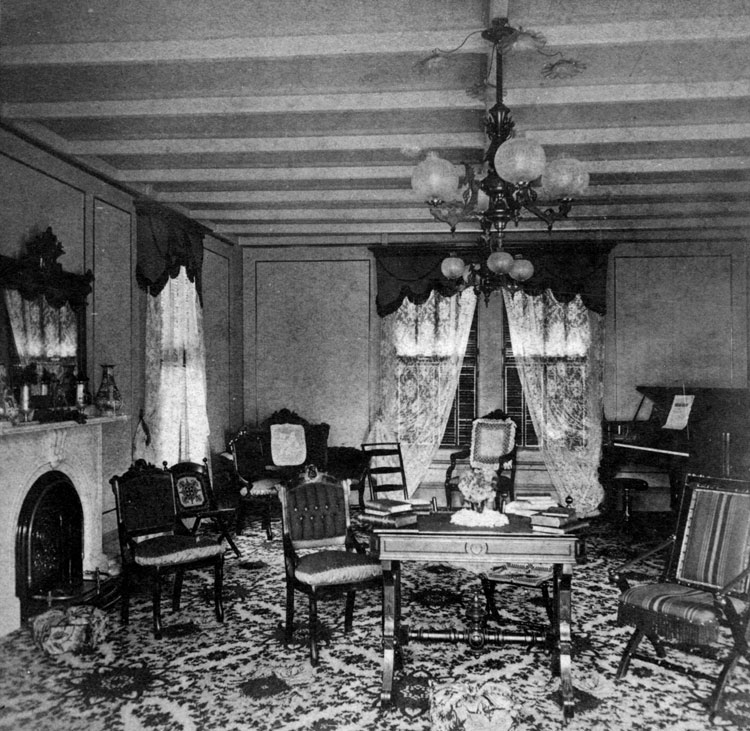

Many doctors, such as Dr. R. E. Gray, a surgeon in Garden City, Kansas, in 1901, decorated their businesses to resemble their patients’ own parlors (Figure 3). Patterned rugs muffled sound, and decorative papers enlivened the walls and ceilings. In Dr. Gray’s office, an ornate carved mirror hung above a shelf covered with lace, and a bed draped with a floral fabric canopy was placed in the corner next to an upholstered bentwood rocking chair. A desk and bookcase full of papers and heavy tomes presented the doctor’s knowledge and business acu men. Only the porcelain bowls, medicine cases, instruments, and dressings attached to a nearby portable pipe-metal rack betrayed the fact that this was not a room in a private American home. Middle-class women, highly attuned to the importance and nuances of appearances, would have read the stylish room as a safe zone of respectability (Figure 4).[13]

Figure 4. Interior of the H.A. Tucker House, a typical middle-class parlor on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts about 1880. Courtesy of Historic New England.

Figure 4. Interior of the H.A. Tucker House, a typical middle-class parlor on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts about 1880. Courtesy of Historic New England.

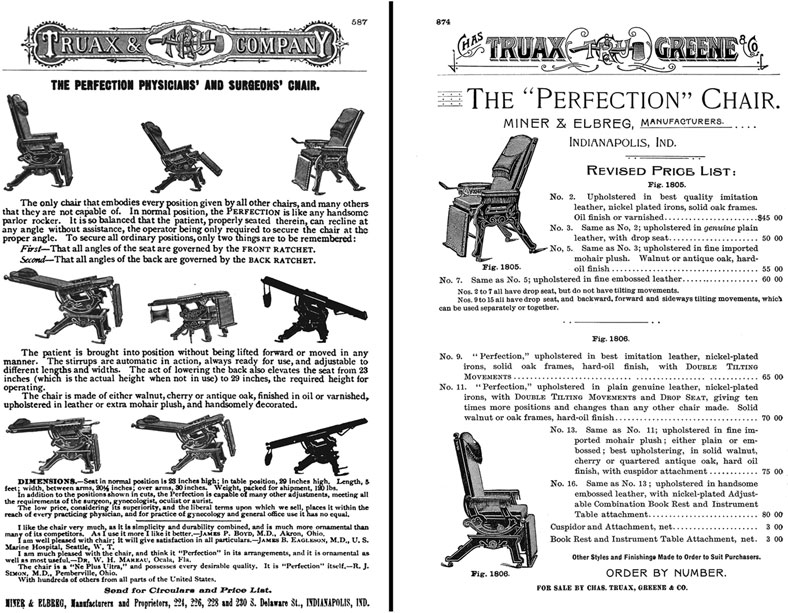

Manufacturers disguised clinical equipment as parlor furniture to help physicians enhance their aesthetic presentation.[14] The Perfection Chair Company’s examination table in its passive form resembled a sitting room center table. Dr. Gray owned a top-of-the-line model that sold for eighty dollars in 1893 and featured a dark “sixteenth century finish” on fashionable quarter-sawn oak, embellished with hand-carved floral decorations, leather cushions, and a full cabinet with zinc-lined drawers (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Perfection Chair Company advertisement, 1893. Charles Truax & Co., Price List of Physicians’ Supplies, 6th Edition, Chicago, 1893.

The least costly version, with imitation leather, no carving, and no cabinets or drawers, was still expensive at fifty-five dollars, three times the typical price of a non-adjustable, white-enameled, wrought-iron hospital table of comparable size.[15] Later versions of the Perfection Table were even more decorated, with neo-classical columns and a sinuously curved apron that exuded superior elegance and taste (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Perfection Chair Company advertisement, 1893. Charles Truax & Co., Price List of Physicians’ Supplies, 6th Edition, Chicago, 1893.

The least costly version, with imitation leather, no carving, and no cabinets or drawers, was still expensive at fifty-five dollars, three times the typical price of a non-adjustable, white-enameled, wrought-iron hospital table of comparable size.[15] Later versions of the Perfection Table were even more decorated, with neo-classical columns and a sinuously curved apron that exuded superior elegance and taste (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Convertible examination table, 1910.

Doctors of BC MedicalMuseum.

Once a patient lay calmly arrayed on the tabletop, a physician opened cabinets and drawers to reveal trays of scalpels, forceps, clamps, bandages, and other implements. With a simple motion, the back- and foot-rests raised together, and the convenient foot pedals tilted the top at various angles. Organized at-hand storage served the diverse needs of turn-of-the-century general practitioners who provided a gamut of services, from apothecary care, first aid, and treatment of everyday illness to gynecological exams and surgery.[16] Patients would have interpreted the solidity and ornamentation of the Perfection Table as indicative of a high-cost, luxury item that signified the doctor’s privileged status and permanence in the community. The owner of an expensive and heavy examination table was unlikely to flee in the dead of night like the charlatans that frequently moved long distances to evade detection by authorities. A quack could purchase the table, just as he could a degree, but it was not so easy to assemble an elegant Victorian parlor in which to place it.

Figure 6. Convertible examination table, 1910.

Doctors of BC MedicalMuseum.

Once a patient lay calmly arrayed on the tabletop, a physician opened cabinets and drawers to reveal trays of scalpels, forceps, clamps, bandages, and other implements. With a simple motion, the back- and foot-rests raised together, and the convenient foot pedals tilted the top at various angles. Organized at-hand storage served the diverse needs of turn-of-the-century general practitioners who provided a gamut of services, from apothecary care, first aid, and treatment of everyday illness to gynecological exams and surgery.[16] Patients would have interpreted the solidity and ornamentation of the Perfection Table as indicative of a high-cost, luxury item that signified the doctor’s privileged status and permanence in the community. The owner of an expensive and heavy examination table was unlikely to flee in the dead of night like the charlatans that frequently moved long distances to evade detection by authorities. A quack could purchase the table, just as he could a degree, but it was not so easy to assemble an elegant Victorian parlor in which to place it.

To decorate an ornate Victorian parlor demanded specialized knowledge and the time and financial resources to select from a wide range of industrially produced furnishings available in stores and through mail-order catalogs. Books and magazines published in the second half of the nineteenth century, such as Charles Eastlake’s Hints on Household Taste, gave women advice on how to choose and arrange objects to create a tasteful interior, but authors also offered advice that associated décor with morality.[17] In their 1869 guide to household management, the Beecher sisters counseled that interior aesthetic “contributes much to the education of the entire household in refinement, intellectual development and moral sensibility.”.[18] Doctors installed a decorated examination table at the heart of a parlor-like medical office to convey erudition and decency. The parlor table was a purposely symbolic object—the focus of the public reception room in the home.[19] In 1891, a columnist in The Decorator and Furnisher ascribed the persistence of the parlor center table to its semantic importance: “as orthodox as the hymn book … The piece de resistance of the room” imbued with ideals “other than that of convenience and taste.”[20] To strengthen the perception of their medical expertise, doctors leveraged middle-class women’s aesthetic expertise.

Figure 7. In the early twentieth century, doctors installed examination chairs evocative of platform rockers like the furniture in the offices of Dr. John W. Thompson in Sutton, Nebraska in 1914 and Maximilean E. Schmidt in Boonville Missouri. Nebraska State Historical Society, and The State Historical Society of Missouri.

Figure 7. In the early twentieth century, doctors installed examination chairs evocative of platform rockers like the furniture in the offices of Dr. John W. Thompson in Sutton, Nebraska in 1914 and Maximilean E. Schmidt in Boonville Missouri. Nebraska State Historical Society, and The State Historical Society of Missouri.

Manufacturers also produced a compact and similarly disguised examination chair that converted into a surgeon’s table (Figure 7). In its upright position, an examination chair resembled a mechanical platform rocker, a fashionable furniture form in the middle-class parlor, particularly associated with women (Figure 8).[21] An 1890 advertisement for the Perfection Chair Company’s model illustrated a variety of orientations, and described its “normal” or upright position as “like any handsome parlor rocker.”[22] Like the examination table, the chair was offered in a number of grades, from the most expensive at $80 in ornamented walnut, cherry, or antique oak with embossed leather, to the least expensive at $45 (Figure 9).

Figure 8. Folding Platform Rocker by E. W. Vaill, 1883, and a salesamn's model of the Perfection Chair. © Philip Carlino and Tizzano Museum.

Figure 8. Folding Platform Rocker by E. W. Vaill, 1883, and a salesamn's model of the Perfection Chair. © Philip Carlino and Tizzano Museum.

Figure 9. Perfection Chair Company advertisements, 1890 and 1893. Charles Truax & Co. Price List of Physicians’ Supplies, 5th Edition, Chicago, 1890, and 6th edition, 1893.

Figure 9. Perfection Chair Company advertisements, 1890 and 1893. Charles Truax & Co. Price List of Physicians’ Supplies, 5th Edition, Chicago, 1890, and 6th edition, 1893.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, licensed medical school graduates gained authority over medicine not only by successfully treating ailments and injuries previously thought incurable, but also by gaining Americans’ trust within the decorated confines of the doctor’s office. Medical practitioners camouflaged offices as parlors to reassure middle-class mothers and wives who associated medical facilities with poor health outcomes and unsavory people. Convertible examination tables and surgical chairs disguised as domestic furniture did more than just save space in cramped offices; the furniture leveraged the visual expertise of middle-class women and their responsibility for creating a moral home to communicate competence. A cluttered domestic parlor seems a surprising setting for a medical practice, but at the turn of the twentieth century, a scientific approach to medicine had yet to achieve any more legitimacy than had more esoteric methods.[23] Doctors fortified patients’ weak faith in theirability to heal, and distinguished themselves from other practitioners, through furnishings that represented success and privilege.

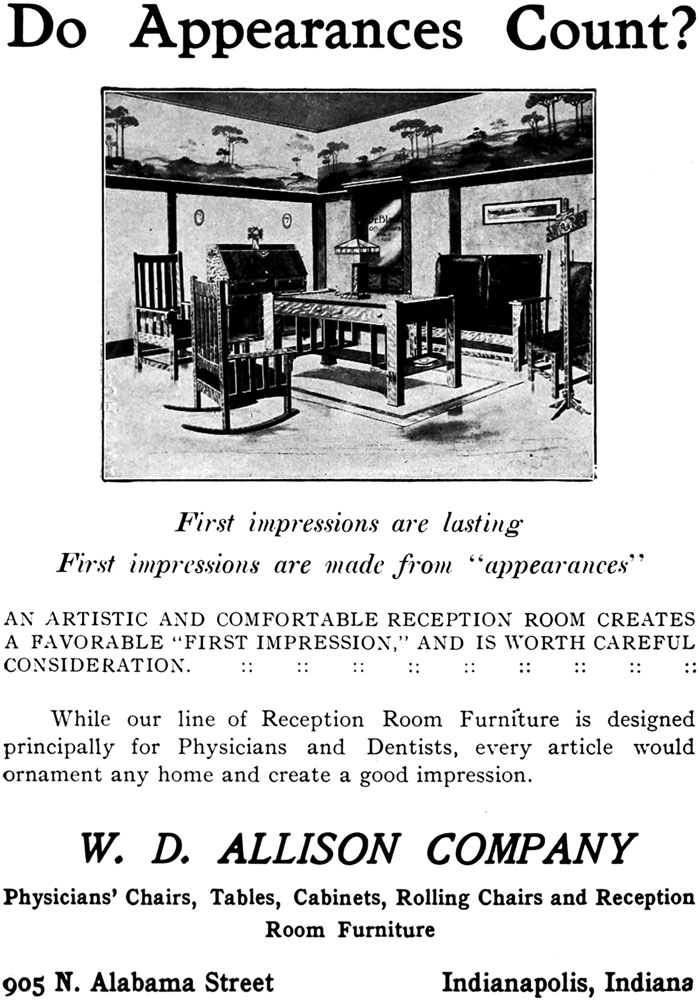

Figure 10. A 1909 advertisement from W. D. Allison, one of the inventors of the adjustable examination table (Indianapolis Blue Book 1910, New York, 1909

Figure 10. A 1909 advertisement from W. D. Allison, one of the inventors of the adjustable examination table (Indianapolis Blue Book 1910, New York, 1909

But this doctor’s office aesthetic—“The Tapestry School,” in the words of a medical furniture salesman in Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith—would not last long.[24] Aseptic hygiene, developed at the turn of the century, soon discouraged wood and upholstery in exam rooms, and encouraged instead the use of highly reflective glass, white enamel, and polished nickel. Whereas in the 1890s such clinical furniture had symbolized institutional health care for the destitute, by the second decade of the twentieth century, metal furniture communicated instead a modern, rational understanding of illness, and the unapologetic presence of laboratory equipment had come to legitimize scientific practice in the eyes of progressive, middle-class consumers.[25] Charlatans, poorly trained doctors, and purveyors of patent medicine had been brought under control through regulation and credentialing, but more traditional healers continued to compete with trained physicians. To undermine the legitimacy of midwifery, herbalism, and other domestic treatments, doctors severed the carefully constructed aesthetic connection between the home and the examination room.[26] By the 1910s, a female nurse or receptionist often welcomed patients into a comfortable, front waiting room, where parlor furniture lived on, promoted by medical equipment manufacturers as still essential for making a favorable first impression (Figure 10). But beyond that domesticated entry chamber now stood a contrasting back room—an efficient examination workshop and laboratory proudly filled with clinical equipment, bright electric lighting, and white furniture that conveyed, as one doctor celebrated, a “fresh sanitary appearance.”[27] Targeted at modern American consumers, the scientific aesthetic reinforced that the proper location for medical care was now the professional office, not the home parlor.

End Notes

1 Middle-class Americans judged class and capability based upon dress, manners, and décor, what Erving Goffman defined “impression management”: a strategy that placed utmost importance on appearances to communicate legitimacy in social situations. See Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Garden City, NY, 1959), 33. Nancy Tomes’s history of American medical practice situates the conversion of patients to consumers within U. S. economic history. See Nancy Tomes, Remaking the American Patient: How Madison Avenue and Modern Medicine Turned Patients into Consumers (Chapel Hill, NC, 2016), 19–47. Also see Christy Chapin, Ensuring America’s Health: The Public Creation of the Corporate Health Care System (New York, 2015), 10–36.

2 It is difficult to classify doctors in the nineteenth century, but for the purposes of this essay, I am focusing on physicians: medical school graduates educated to become general practitioners.

3 J. Marion Sims, Clinical Notes on Uterine Surgery (New York, 1873), 21–3.

4 Charles D. Meigs, Females and Their Diseases: A Series of Letters to His Class (Philadelphia, 1848), 135–6.

5 “Traveling Quack Doctors,” Democrat and Chronicle, Oct. 2, 1885, 4.

6 Paul Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine (New York, 1982), 61–78; David A. Johnson and Humayun J. Chaudhry, Medical Licensing and Discipline in America: A History of the Federation of State Medical Boards (Lanham, MD, 2012), 47; Barbara Rosenkrantz, “The Search for Professional Order in 19th-Century American Medicine,” in Sickness and Health in America: Readings in the History of Medicine and Public Health, 3rd edition, ed. Judith Leavitt and Ronal L. Numbers (Madison, WI, 1997), 219–32; Bernice A. Pescosolido and Jack K. Martin, “Cultural Authority and the Sovereignty of American Medicine: The Role of Networks, Class, and Community,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 29, nos. 4–5 (Aug.–Oct. 2004): 735–56; Lilian R. Furst, Between Doctors and Patients: The Changing Balance of Power (Charlottesville, VA, 1998), 94–5.

7 Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine, 61–78; Tomes, Remaking the American Patient, 20–5.

8 Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine, 79–142.

9 Tomes, Remaking the American Patient, 24.

10 Johnson and Chaudhry, Medical Licensing and Discipline in America, 10; “Medical Education in the United States: Annual Presentation of Educational Data for 1922 by the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals,” Journal of the American Medical Association 79, no. 8 (Aug. 19, 1922), 629–33; Joel D. Howell, “Making a Medical Practice in an Uneasy World: Some thoughts from a Century Ago,” Academic Medicine 72, no. 11 (Nov. 1997): 977–81.

11 “Home and Foreign Gossip,” i, Nov. 18, 1871, 1079.

12 D. W. Cathell, The Physician Himself and Things that Concern His Reputation and Success, 9th edition (Baltimore, 1890), 10.

13 On the meanings American women invested in such décor, see Katherine C. Grier, Culture & Comfort: Parlor Making and Middle-Class Identity, 1850–1930 (Washington, DC, 1988), 22–63, 89–116.

14 W. D. Allison and The Perfection Chair Company, both of Indianapolis, were the most prominent manufacturers of examination chairs and tables, but at least six others firms manufactured nearly identical forms.

15 Charles Truax & Co., Price List of Physicians’ Supplies, 6th Edition (Chicago, 1893), 867.

16 Johnson and Chaudhry, Medical Licensing and Discipline in America, 20; Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine, 41–2.

17 Charles Eastlake was an architect and proponent of the English Art and Crafts movement. His book, published in 1868, was widely read in the United States. Charles Locke Eastlake, Hints on Household Taste in Furniture, Upholstery and Other Details (London, 1868).

18 Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe, The American Woman’s Home, Or, Principles of Domestic Science (New York, 1869), 84. Magazines that provided advice on the creation of aesthetically pleasing and therefore moral homes included Godey’s Lady’s Book, The Ladies’ Repository and Home Magazine, and Harper’s Weekly.

19 The parlor table was the location for the display of religious objects that communicated a family’s piety to visitors. See Grier, Culture and Comfort, 91.

20 Ada Cone, “Aesthetic Mistake in Furnishing—The Parlor Center Table,” The Decorator and Furnisher 17, no. 4 (Jan. 1891): 132.

21 Grier, Culture and Comfort, 185–186.

22 Charles Truax & Co., Price List of Physicians’ Supplies, 5th Edition (Chicago, 1890), 587.

23 Pescosolido and Martin, “Cultural Authority and the Sovereignty of American Medicine.”

24 Sinclair Lewis, Arrowsmith (New York, 1925), 85–7. The fictional Dr. Gaeke, vice president of the “New Idea Medical Instrument and Furniture Company of Jersey City,” gives a speech titled “The Art and Science of Furnishing the Doctor’s Office,” describing “The Tapestry School” versus the “Aseptic School,” in doctor’s office furnishings styles.

25 Ibid.

26 Tomes, Remaking the American Patient, 27, 38.

27 Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine, 76; “The Business Side of Practice,” The Osteopathic Physician 25, no. 3 (Mar. 1914): 5–6.