Designing a career

Inspiring Women: Selected Designers from Parsons’ Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Archives,

March 26–27, 2010

Figure 1. Left: Mildred Orrick (artist), Norman Bel Geddes (commissioner), Costume designs for Norman Bel Geddes's production of Aristophanes' Lysistrata, circa 1930. Right: Mildred Orrick (designer), Green Satin Wrap Dress with Red Lining, 1934 – 1937. The New School Archives.

Women have studied at Parsons in large numbers since the school’s founding, but many graduates discovered there was not a clearly defined career path for them to follow. This uncertainty was due not only to the novelty of women in professional careers, but also to the recent birth of design as a profession. Although Parsons’ graduates were given courses in both artistic and business skills, there was no established hierarchy of positions in industry for obtaining the depth of experience needed to achieve success. To gain the experience they needed, the women in the exhibition forged unique trails in education, corporate and freelance design, fine arts, and marketing, while navigating male-dominated business leadership and familial relationships.

The women in the exhibition managed the intersection of family and professional life in several ways. The demands of a marriage and family may have limited their creative endeavors, but also offered new opportunities for collaboration and mentorship. In her early career, Mildred Orrick designed costumes in collaboration with Norman Bel Geddes, the noted industrial designer (Figure 1). She also collaborated with her architect husband on stage productions, but went into “semi-retirement” when she had children. She continued to provide illustrations for Harper’s Bazaar, eventually returning to fashion design to lead her own design firm. For Joset Walker, the raising of a family took precedence over career ambitions. She withdrew from leading her own well-known design firm to join the suburban wives who were previously her clientele. The pressure of serving as art director at major publications while struggling to conceive led Cipe Pineles to attempt suicide, yet she credited the collaboration and support of her husband as important contributions to her success. Esta Nesbitt and Andrée Golbin were both married to artists who acted as supportive collaborators and sounding boards for their projects and pursuits.

Figure 2. Joset Walker featured in a Camel cigarette magazine advertisement, with the attributed quote, "In these days of hard work, I appreciate a mild cigarette more than ever…”, 1942. The New School Archives

Husbands and mentors provided support and shared knowledge, but it was the women’s entrepreneurial spirit that led them to seek out new work opportunities for learning and advancement. Claire McCardell, Joset Walker and Mildred Orrick are among the most well-known Parsons graduates of the middle twentieth-century (Figure 2). (See Alexandra Anderson’s essay about Claire McCardell in this catalog for a more in-depth discussion of her career and their relationships.) Both Walker and Orrick rose to prominence designing costumes for Broadway and Hollywood in the 1930s. Costume design was a significant program of study at Parsons during their time at the school. Designing for the stage and screen freed Walker and Orrick from the constraints of Parisian style that was still driving American fashion at the time. Because theatrical costumes were not limited by the requirements of mass-appeal or the technical requirements of large-scale production, the women were able to experiment with new forms and unusual materials to create dramatic statements. The spirit of innovation, theatricality and independence from convention served the designers well as they moved from costumes to leading their own design firms in the 1950s and went on to define a uniquely American fashion sensibility. Both returned to Parsons as teachers and critics to share their experiences with another generation of designers.

During the same mid-century period, there were other Parsons graduates whose achievements were lower profile but whose career paths are just as interesting. Among the women in the exhibition are several designers who worked at prominent women’s magazines. Cipe Pineles, Margaret Hodge and Bea Feitler held executive positions in the creation of publications such as Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Glamour, Seventeen and Ms. As such, they were influential in reflecting and shaping the visual representation of women during the second half of the twentieth century.

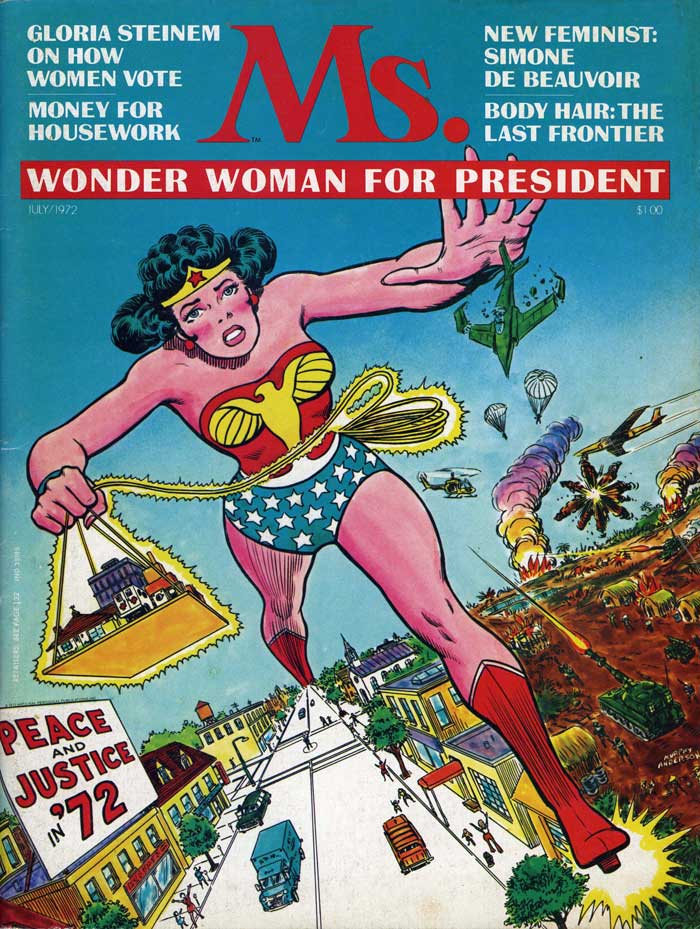

Figure 3. Bea Feitler (designer),Inaugural cover of Ms. July 1972.

As Ms. magazine’s first art director in the early 1970s, Bea Feitler designed many iconic and groundbreaking magazine covers for the successful feminist publication. Her later career included freelance work for Rolling Stone and Vanity Fair, as well as costumes and programs for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (Figure 3).

Figure 4. Advertisement for Tab Soft Drink and Mr. Dino Fashions. The New School Archives

Margaret Hodge’s degree in Costume Design and Illustration from Parsons led her on a path not to fashion design or costume design, but to fashion marketing. After serving as director of fashion marketing for Vogue, she moved on to her own promotions company for fashion and cosmetics. She specialized in using popular culture as a bridge to selling fashion. Hodge worked with major film studios to tie fashion designs to blockbuster films through department store fashion shows and press releases. But she also created unique advertising campaigns linking well-known fashion designers to other industries, with designers abstracting product logos into fashionable clothing for women that tied into the culture of the products. For Tab cola, Hodge connected body-hugging designs to a new body consciousness for women and the growing market for diet soft drinks (Figure 4). For Bahamas Airways, she used jet-set fashion and stewardess uniforms to sell fashions for the world traveler.

Figure 5. Cipe Pineles (designer), Parsons School of Design poster

Cipe Pineles’ award-winning presentations of assertive young women in magazines like Glamour, Charm and Seventeen influenced a generation of readers. She started her career in the early 1930s using her color sense to design textiles that caught the attention of the wife of Condé Nast. The contact led her to a job working as an assistant to M. F. Agha at Vogue and Vanity Fair. For five years Agha served as mentor to Pineles, teaching her the technical skills of typography and experimental layout. The knowledge Pineles absorbed guided her in her leadership role as the first art director for Seventeen in 1947. Meanwhile, she married William Golden, a graphic designer who would go on to become art director at CBS. Golden and Pineles were a good match. Holding similar roles in different media contexts, they were able to share experiences and knowledge that enhanced both of their careers. In the 1960s, Pineles’s path took another turn: she began teaching at Parsons, and in 1970 became the school’s director of publications (Figure 5). She had always viewed the form of her layouts to be in support of the editorial function of the magazines. An emphasis on content as a driving force in graphic design was a modernist mantra that she taught during her twenty-five year career at Parsons, launching students on their own journeys to success.

There are others in the exhibit who used their degrees from Parsons to design career paths across several different occupations. Lea Hoyt graduated with a degree in Graphic Advertising and Industrial Design in 1933 and enjoyed a forty-five year career in textile design for several large manufacturers, including Ameritex, Burlington Industries and Cohn-Hall-Marx (Figure 6). After her retirement from industry she continued to work well into her 80s as a freelance designer, creating patterns for wallpaper, greeting cards and paper products. She also exhibited fine art paintings.

Figure 6. Lea Hoyt, Geometric Goache, 1940-1979. The New School Archives.

Figure 6. Lea Hoyt, Geometric Goache, 1940-1979. The New School Archives.

In the course of her successful fashion illustration career, Esta Nesbitt tailored style and media to best suit the fashions she represented. From elegant line drawings and pastels for lingerie to expressionistic red gouache on newspaper for sixties go-go fashions (Figure ), her fluid and bold images translated well into newspaper and magazine advertisements. A fine artist at heart, Nesbitt also experimented with a variety of printmaking techniques such as xerography to create award-winning illustrations for children’s books. Her path eventually led her to Parsons, where she served as an instructor from 1964 through 1974.

Figure 7. Ester Nesbitt, lingeree sketches and . The New School Archives.

Figure 7. Ester Nesbitt, lingeree sketches and . The New School Archives.

Andrée Golbin graduated in 1943 with a certificate in Advertising and Industrial Design. She started her career as a promotion art director at Mademoiselle and led a thriving career as a freelance graphic designer, book and magazine illustrator. Her illustrations for the “Easy Reader” series of children’s books are familiar to Americans who were children in the 1960s and 1970s. Golbin was also a recognized and successful fine artist whose work was sold in several New York galleries and appeared in significant group and solo shows. In 1976, she was recognized for her creativity with an International Woman of the Year award from the United Nations. She, too, returned to teach at Parsons.

The unique paths created by these women may not seem unusual today, when moving between jobs and freelancing to gain experience have become established practice among design professionals, and when the demands of family pressure are somewhat more clearly understood. But during a time when there were few leadership positions open to women in the professional fields, the risk of changing jobs and losing professional momentum was magnified. With a combination of entrepreneurial spirit, business knowledge, and creativity, these pioneering women blazed trails, paving the way for the next generation of designers in order that they could set off on their own paths toward successful careers.